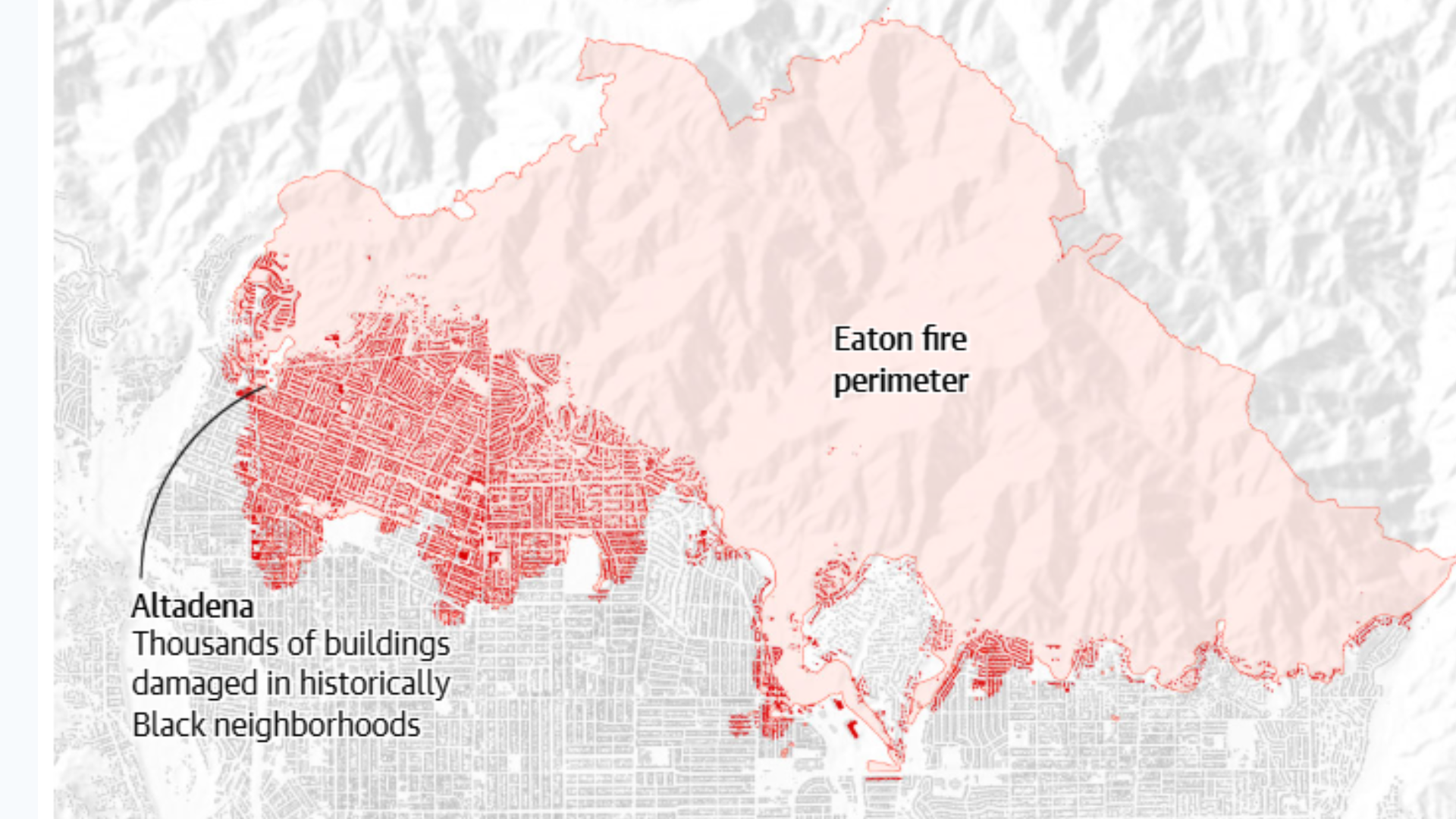

After burning for nearly a month, the LA wildfires have finally been contained, leaving devastation in its wake. The Eaton Fire directly east of Los Angeles ravaged 14,021 acres of land and leveled much of the historic community of Altadena. The Public Works Partners team is proud to have a growing office in Pasadena, just ten minutes south of Altadena and the southernmost reaches of the Eaton Fire. As the long rebuilding process begins, we want to tell the often-overlooked story of Altadena and share our vision for an equitable and community-forward recovery.

What we are seeing on the ground:

The Eaton Fire has devastated Altadena, claiming 17 lives and destroying over 9,000 structures, including homes, cultural landmarks, small businesses, and community institutions. Altadena’s Black residents, which make up nearly 20% of the historically Black community, have been disproportionately affected by the wildfires. According to a recent UCLA study, 61% of Altadena’s Black households were within the Eaton Fire perimeter, compared to 50% of non-Black households. Moreover, 48% of Altadena’s Black homes were flattened by the wildfires, compared to 37% of non-Black homes.

This level of destruction poses a major challenge to the future of generational wealth and homeownership for Altadena’s Black residents, who have amassed both residential and commercial assets in the community over decades.

What we know about the community:

Altadena is a multi-racial and culturally vibrant community in Los Angeles County 15 miles northeast of Los Angeles. A haven for Black families, artists and the world’s iconoclast—including Jackie Robinson, Octavia Butler, Charles W. White, Eldridge Cleaver, and Sidney Poitier—Altadena was originally founded in 1887 as a primarily White rural suburb before transforming into a thriving, multi-racial community during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and ’70s.

At its peak in the 1980s, Altadena was 43% Black. Today, Altadena remains a diverse and dynamic place, with a population of 43,000 people, 58% of whom are people of color, including 18% who are Black. Despite shifting demographics, it continues to stand out as a rare haven of Black homeownership in Los Angeles County. According to LAist, “Altadena is one of those rare places in Los Angeles County where people of many backgrounds and ethnicities have been able to afford the American Dream of homeownership.” Census data indicates 75% of Black Altadenans own their homes, which is nearly double the national rate.

This legacy of diversity, homeownership, and cultural significance makes Altadena a unique and enduring community in the fabric of Southern California.

How did this community come to be?

Altadena emerged as a haven for Black communities at a time when racial exclusion was the norm across much of the United States. While redlining and sundown laws—policies that restricted where Black families could live and when they could occupy public spaces—were common elsewhere, Altadena followed a different trajectory. Unlike many neighboring areas, Altadena was not shaped by the same exclusionary planning tools that segregated cities nationwide.

With the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and the subsequent outlawing of racial covenants, White flight to the suburbs accelerated, opening opportunities for Black families to purchase homes in areas previously inaccessible to them. In many cities, this shift was met with hostility, but in Altadena, the transition unfolded with relatively little resistance. As a result, Black residents were able to move more freely and build a thriving community, unburdened by the harsh restrictions that persisted elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Pasadena—founded as an all-White enclave—was considered by some to be a more desirable location at the time. However, as demographics changed, Altadena flourished into a richly diverse and multi-racial community. Without the aggressive enforcement of racist housing policies, a unique and complex city took shape—one defined by cultural vibrancy, resilience, and a legacy of inclusion.

Today, Altadena stands as a testament to what is possible when a community grows beyond the confines of exclusion and segregation. Its history reflects both the struggles and triumphs of those who sought a place to call home, free from systemic barriers, and its layered past continues to shape its identity as a place of opportunity and belonging.

Recovery Challenges & Role of Post- Disaster Planning:

The Eaton Fire not only devastated homes and landscapes but also intensified existing economic challenges, particularly the rising cost of housing. According to Veronica Jones, president of the Altadena Historical Society, fears of gentrification loomed over Altadena even before this disaster, as skyrocketing housing prices threatened the ability of long-term residents to remain in their community. Now, amid the rebuilding process, concerns have deepened: not just about affordability but also about preserving the cultural and historical fabric that has defined Altadena for generations.

Residents are determined to rebuild, but many are asking whether they can restore what was lost while still protecting the community’s identity. According to ABC News, worries about gentrification have already begun to surface. For longtime residents like Kim Jones, who tragically lost her home during the wildfires, the stakes are deeply personal. Jones, whose family has lived in Altadena for four generations, sees the current crisis as a continuation of historical struggles. Her family moved to Altadena in the 1960s to escape racism and segregation in the South, seeking a place where they could build a future. Now, she fears that some residents will be pressured into selling their land at undervalued prices. “But there’s no quick sale [of our land],” she told ABC News. “There’s no quick sale because California is expensive to live in. I want my family home to be a family home for the next generation and the generation after that.”

Rebuilding, while essential, has historically been a driver of gentrification. The question now is whether policies and zoning regulations can be shaped to protect Altadena’s long-term residents. As the recovery process unfolds, the community is grappling with how to ensure that rebuilding does not come at the cost of erasing the very people and histories that make Altadena unique.

What are the comparisons and lessons learned from Katrina?

The scale of the Los Angeles wildfires is staggering, with thousands of homes and businesses destroyed across Southern California. Preliminary damage maps reveal a level of devastation reminiscent of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when entire neighborhoods were wiped away.

“This is your Hurricane Katrina,” former Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Administrator Craig Fugate told the Los Angeles Times, underscoring the magnitude of the crisis. California Governor Gavin Newsom has warned that early recovery costs are expected to surpass the $201 billion in damages caused by Katrina—the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

Compounding the crisis is the growing instability of the state’s insurance market. Since 2018, more than 100,000 Californians have lost their homeowners’ insurance, leaving many residents unprotected and financially vulnerable in the face of disaster. As the region begins to grapple with recovery, the question remains: How can California rebuild in a way that not only restores what was lost but also strengthens communities against future catastrophes?

The planner’s role:

The true legacy of this tragedy will be defined by how we choose to rebuild. Urban planners have a critical role in ensuring that recovery efforts do not come at the expense of the community’s identity, history, and cultural significance. Equitable rebuilding means implementing policies that protect long-term residents from displacement, such as mortgage moratoriums that provide financial relief and safeguards against exploitative redevelopment. By prioritizing affordable housing, community-led planning, and zoning measures that prevent speculative buyouts, planners can help restore what was lost while ensuring that those who call this place home can continue to do so for generations to come.