Lovers of low-budget New York City cult films might recognize the name Timothy “Speed” Levitch as the hero of The Cruise, a 1998 documentary that follows the local folk-philosopher, historian, and double-decker tour bus guide as he traverses the streets of Manhattan and sermonizes to the camera and anyone who’ll listen. At one point, Speed delivers a polemic against one of the most unforgivable and mistakenly overlooked qualities of Manhattan:

“The grid plan emanates from our weaknesses,” he says while walking down a Soho sidewalk, backdropped by graffiti-clad walls, “this layout of avenues and streets, this system of ninety degree angles—to me the grid plan is Puritan, it’s homogenizing, in a city where there is no homogenization … only total existence, total cacophony.”

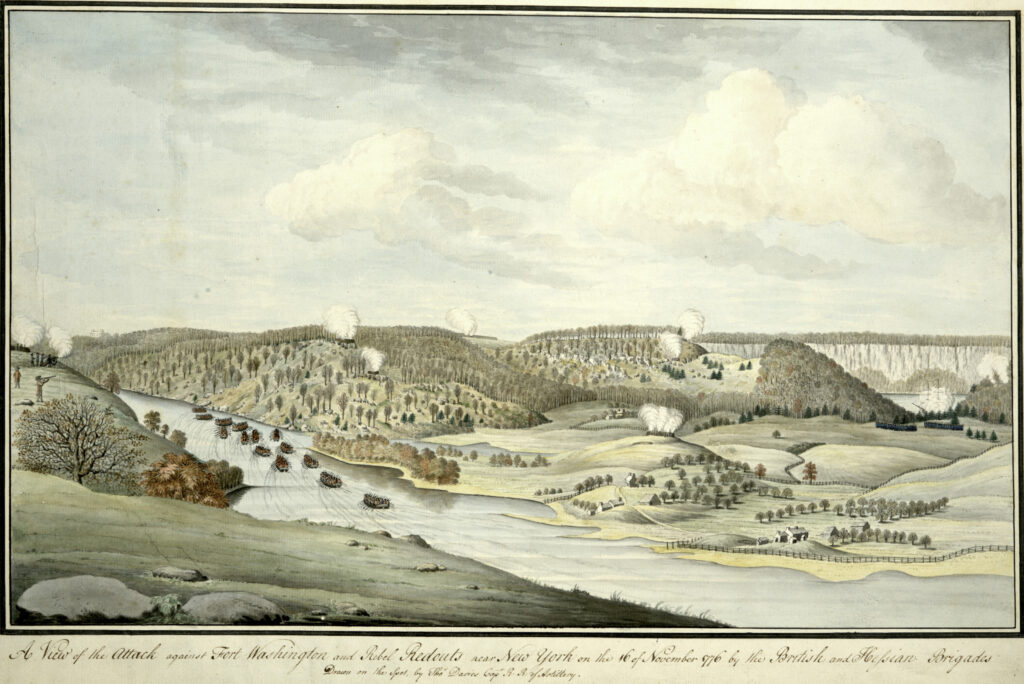

For Levitch, Manhattan’s grid is the tragic apogee of “civilization,” to use a word he uses frequently—an attempt to superimpose order and harmony onto an essentially cacophonous and dissonant city. But while Levitch characterizes this sacred chaos as part of the spirit of New York, residents of the City’s colonial downtown around the turn of the nineteenth century might have found this noise oppressive: imagine cramped quarters, muddy roads and alleyways, contaminated water, the ever-present smell of raw sewage. The above painting of lower Manhattan’s notorious Five Points intersection depicts a lively scene of debauchery, disorder, and drunkenness—the antithesis of the grid. Upon visiting the same area some years later, Charles Dickens saw “poverty, wretchedness, and vice … all that is loathsome … narrow ways diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth.” The commissioners would not have disagreed with Levitch: their mandate was human progress, advancing civilization, and pushing the city forward into the new century. Their grand solution of rectilinear streets and avenues was unprecedented in its uniformity and scale, and its gradual implementation over fifty years across countless city administrations was something of a miracle, but whether the grid advanced or curtailed the “progress” of the city has been debated since those first few roads were opened north of Houston Street.

“The early planners succeeded,” wrote the historian Lewis Mumford in 1932, “in putting their city in a straight-jacket from which it has not escaped, from which perhaps it can never escape.”

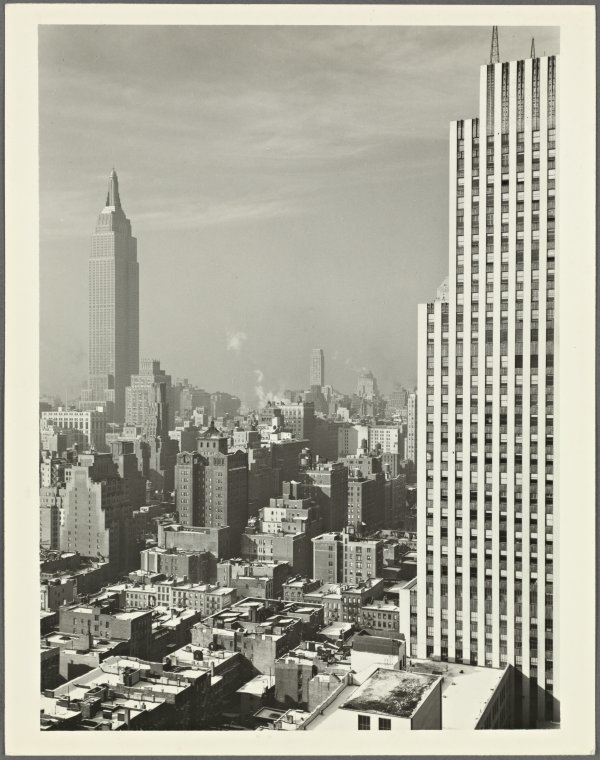

Since then, the grid has managed to resist a few piecemeal twentieth-century disruptions, and, to this day, remains the single most definitive city planning exercise in New York City’s history—if you live or spend time in Manhattan, you move through space in a series of right angles. You look up at a wall of buildings, and as you gaze toward the horizon, you see them all converge on a single vanishing point. Almost anywhere you go on the island, in any direction you look, your experience will be exactly the same.

That most New Yorkers are blind to the profundity of this phenomenon is just more evidence that the grid is a spiritual anesthetic, argues Levitch. Is it worth rethinking the grid, two hundred years later?

If so, we may as well go all the way to the beginning. Does the grid’s origin story live up to its legacy?

Before the Grid

New York City, in the early 1800s, was getting crowded. Manhattan’s population jumped from around thirty to sixty to ninety thousand between the years of 1790, 1800, and 1810, respectively, and it was in response to this rapid settlement that the Common Council, NYC’s nascent governing body, acknowledged that the heretofore organic and haphazard approach to street design would not support this rate of growth for much longer. The council petitioned Albany for help “laying out streets … in such a manner as to unite regularity and order with the public convenience and benefit and in particular to promote the health of the City.”

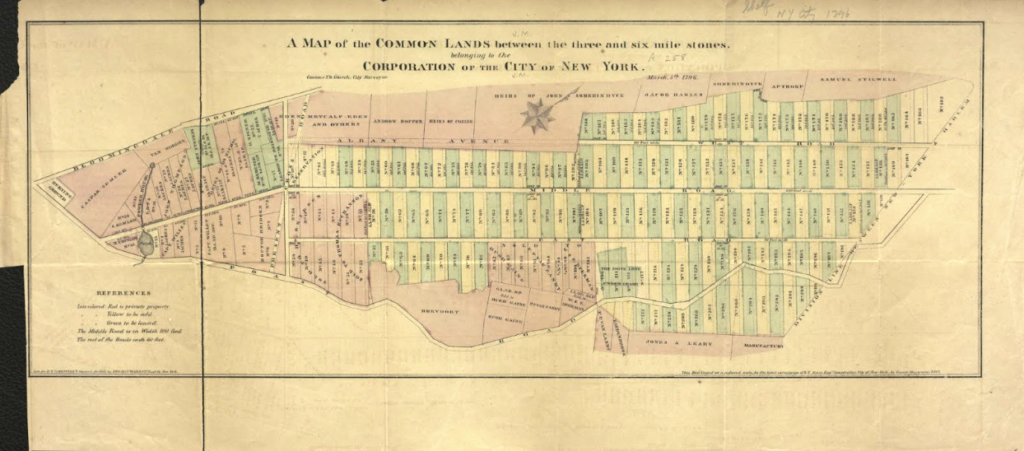

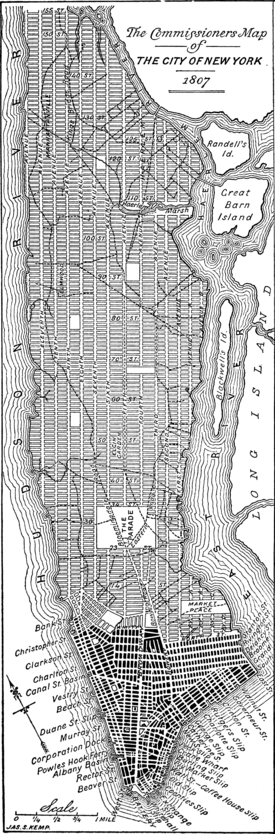

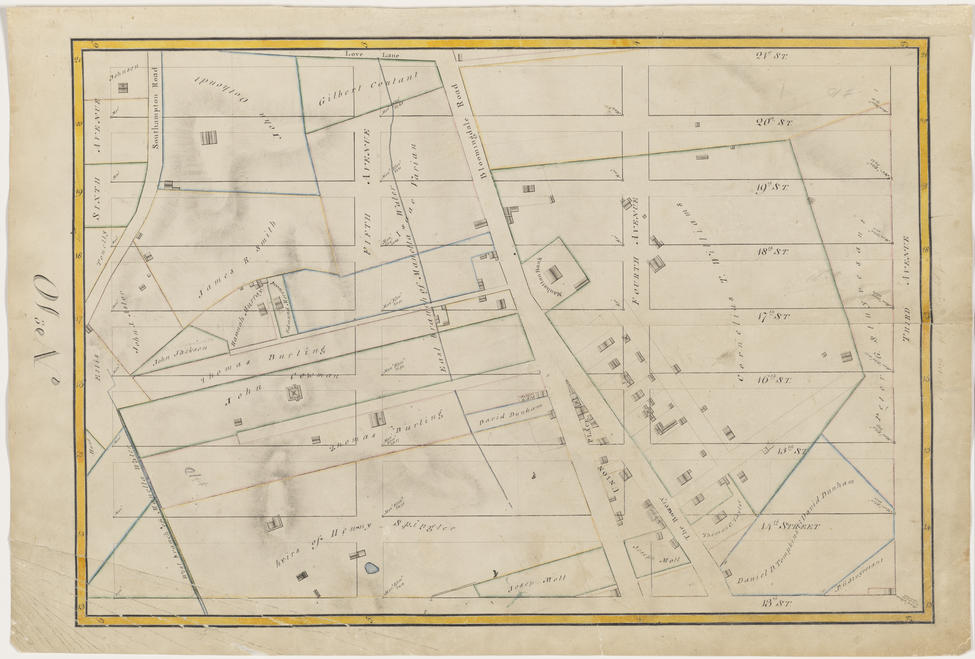

Although it was unclear whether the Common Council would have the authority or the money to implement a comprehensive street plan, Albany nevertheless assigned three “commissioners” to the task: Gouverneur Morris, John Rutherford, and Simeon Dewitt. With a four-year deadline, and while distracted by other projects—most notably the Erie Canal—they borrowed heavily from existing work. By 1796, the City had already surveyed the rugged common lands of Manhattan’s interior twice; these first two surveys, conducted by Casimir Goerck, would introduce New York to the idea of vertical avenues and rectangular, five-acre parcels. Goerck’s surveys were never meant to be a comprehensive street system, only a quick and easy way to subdivide City-owned common lands into sellable lots, but they would offer the commissioners a simple and replicable framework that was, it seems, good enough for the rest of the island.

In 1807, John Randel Jr, the commissioners’ twenty-year-old chief surveyor, got to work—though not without encountering a few challenges along the way. “On one occasion,” said Morris in his 1811 remarks, “the surveyors were driven off the land by a woman selling vegetables by a barrage of artichokes and cabbages.” In his own words, Randel was “was arrested by the Sheriff, on numerous suits instituted … for trespass and damage by … workmen, in passing over grounds, cutting off branches of trees. &c., to make surveys under instructions from the Commissioners.”

In hindsight, Randel’s final map looks awfully familiar, the commissioners never acknowledged Goerck’s previous surveys. In fact, they did not mention Goerck at all, despite placing their Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Avenues exactly where he marked his East, Middle, and West Roads, etching sixty-foot wide cross streets between each parcel, and more or less copying and pasting until hitting each river, except for the small piece of land above 155th street and existing downtown at the Island’s bottommost tip. Why the commissioners failed to mention the grid’s most important influence might offer some insight into how they felt about the quality of their work.

Why a Grid?

Since historian Edward K Spann published his now oft-cited essay “The Greatest Grid: The New York Plan of 1811” in 1988, the “greatest” label has stuck. But it was actually New York’s relative unimportance as a religious or political center that led to the grid’s genesis. The informal streetscape of early 19th century downtown Manhattan stood out from other colonial-era American cities, many of whose street designs preceded their actual settlement and whose layouts were, according to Spann, “imbued with socio-political and aesthetic concerns.” William Penn’s Quaker humility informed Philadelphia’s simple geometry and balance, and in his plans for Washington DC, Pierre L’Enfant expressed the ideals of democracy and separation of power by setting the major national landmarks and government houses on opposite ends of diagonal boulevards. In his own words, this served to “connect each part of the city… by making the real distance less from place to place, by giving them reciprocity of sight and by making them thus seemingly connected.”

In New York, the commissioners eschewed both aesthetics and ideology. In his very brief remarks in 1811, Morris notes that the first order of business was to decide on the “form and manner” of the street plan, and “whether they should adopt some of those supposed improvements by circles, ovals, and stars, which certainly embellish a plan, whatever may be their effect as to convenience and utility,” as in Washington DC and many Baroque-era European cities, like Paris. Their answer: “In considering that subject they could not but bear in mind that a city is to be composed principally of the habitations of men, and that straight-sided and right-angled houses are the cheapest to build and the most convenient to live in.” Put shortly, New York did not require any special treatment.

Uninterested in mimicking Paris or Washington DC, New York was mostly anxious to be rid of itself—its old, crowded, dirty, smelly self. Spann writes of the already-urbanized area, “most of its streets were narrow, crooked, crowded, and so poorly organized as a system that one visitor complained that it took at least a month to learn one’s way around town.” In the public imagination, this was directly linked to poor public health; the yellow fever outbreaks of 1803 and 1805 only preceded the project’s launch by a few years. While the grid’s uniform, wide streets were a rebuke of the existing teeming and unsanitary colonial downtown, the lack of public space is cause for skepticism. One would assume that the commissioners would prioritize proper ventilation to prevent noxious miasmas from descending on the good people of the City. Morris acknowledges this concern and then dismisses it—in doing so he reveals the plan’s true objectives. Parks would be unnecessary, he says, thanks to “those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan island in regard to health and pleasure as well as to the convenience of commerce.”

Commerce, according to Morris, is the grid’s guiding principle. “When, therefore, from the same causes the prices of land are so uncommonly great, it seems proper to admit the principles of economy to greater influence than might, under circumstances of a different kind, have consisted with the dictates of prudence and the sense of duty.” Without those superfluous stars and diagonals, and with only a few public spaces and markets, the commissioners could squeeze every possible square foot of future real estate from the lands of Manhattan. Deciding between duty and economy, the commissioners chose the one with higher dividends.

“How this City Marches Northward!”

New York’s streets would “open” over the next half-century; each of the twelve avenues would creep northward a few blocks at a time, some quicker than others, steadfastly advancing through the many legal and natural obstacles in their path. Landowners whose properties were cut into pieces ( held financially responsible for paying a percentage of the cost of expanding streets through expropriated territory) mobilized early and often against the grid. But these attempts were unsuccessful, and the court’s decisions would not only help codify the City’s authority over planning and maintaining streets, but necessitate a local government that was powerful enough to execute the plan.

Failing in court, some of these landowners took to sabotage. John Randel and his team of surveyors found, on countless occasions, his iron and marble monuments used to mark intersections defaced, destroyed, or disappeared. Randel (referring to himself in the third person) reported that “in 1815, the pegs were destroyed to such an alarming degree as almost to discourage him from ever completing the work.” Other New Yorkers took to rhetoric. “Our public authorities seem unwilling to depart from their leveling propensities,” said Clement Clarke Moore, a Chelsea landowner and writer, “but proceed to cut up and tear down the face of the earth without the least remorse, and, apparently, with no higher notions of beauty and elegance than straight lines and flat surfaces placed at angles with the horizon, just sufficient to suffer the mud and water to creep quietly down their declivities.”

However, many of these landowners, including Moore himself, eventually realized that there was more money to be made in accepting the grid than resisting it. Like it or not, more streets meant more usable frontage and building sites, and the uniformity of plots established a real-estate system that could quickly be replicated repeatedly. By the time Clement Clarke Moore had finished developing his newly reconfigured estate, his personal wealth had grown from an estimated $17,000 to $600,000.

Despite its haphazard origins, the grid would not have been completed had it not benefited enough people—all it had to do was capture the hearts and minds of real estate speculators. Spann writes: “The loudest voice in planning decisions was that of property-holders and businessmen: those decisions that benefited them were approved, and those that did not were dismissed.” Although somewhat reductive and cynical, this kind of skepticism is not uncommon today across policy areas as wide as development and housing, education, criminal justice, and transportation; big moments of restructuring can create opportunities for new winners and losers, and while it is always in the winners’ best interests to make the new system stick, simply beginning the project puts “facts on the ground,” and generates a momentum that can feel impossible to stop.

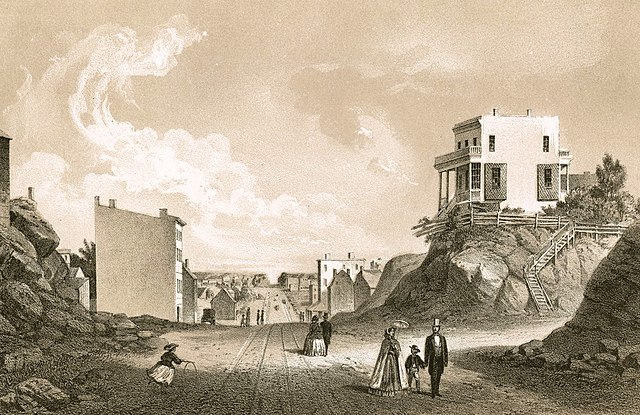

Rock, Water, and Mud

This left only natural phenomena in the grid’s path. The commissioners’ topographically blind map would require substantial grading and leveling of the west side’s outcrops and cliffs, and infill in the east side’s swampy marshes. One might assume that excavated rock from the highlands would be deposited in the lowlands; while this was a common practice, it was not always the case. An observer on First Avenue reported that “it has become dangerous and almost impassable for carriages, owing to the large pits and gullies, which have been occasioned by unlicensed dirt carmen digging up the earth in the middle of the road, and carting it away, to fill in the sunken grounds in that neighborhood.” Filling Manhattan’s creeks and wetlands with rock and soil would require the installation of extensive subsurface sewer systems and create drainage issues that sparked complaints from residents as early as the 1820s, but continue to present, and seem only to get worse with each year.

Perhaps leveling and grading could have been made easier if either the commissioners or John Randel had included proposed elevations of their streets, but without these details, the Common Council assumed the responsibility for determining street grades itself. But it did so on an ad-hoc basis, much to the annoyance of property owners, who often did not know whether new or existing homes would end up at street level when the grid arrived at their doorstep.

Excavating rock was a laborious and expensive undertaking. “The Diluvium is a tough cement of clay, gravel, and boulders, very hard to dig,” wrote historian Issachar Cozzens in his 1843 text Geological History of Manhattan or New York Island. “In digging through 42nd Street, the pickaxes had to be used for every shovelful of this clayey cement which formed what is called, a hard-pan, of about 14 or more feet in thickness.” When handheld tools were insufficient, laborers employed gun powder, and rubble would be hauled away by horse-drawn carts. Progress was slow; meanwhile, Manhattan was filling up.

But after a half-century of draining marshes, shaving hills down to size, and erasing the irregularities from the land, the streets of Manhattan were opened—and despite all the pushback mentioned up to this point, many residents eventually welcomed it. “Our streets have been straightened and widened, our buildings much improved and beautified. Whoever wishes to see the process of city-creation going on—fields converted into streets and lots, ugly cliffs into stately mansions, and whole rows of buildings supplanting cow pastures, may here be gratified.” This person is describing a conquest of civilization over nature. It’s not surprising that Manhattan’s grid was opened just as America’s western frontier was settled.

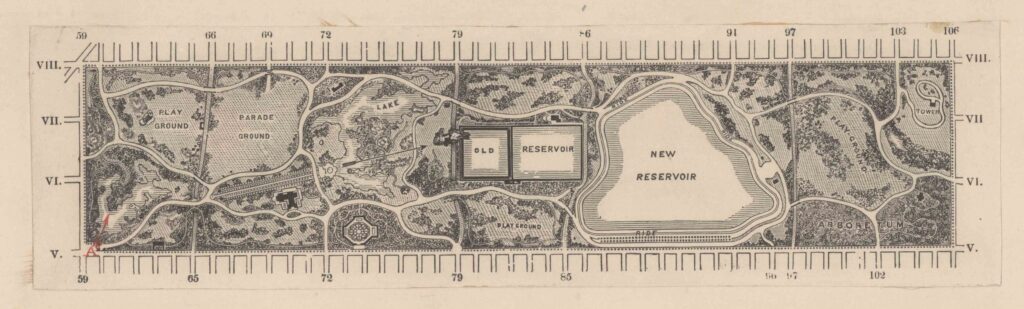

Over the years, the ‘one grand, permanent plan’ would undergo some alterations: most were small, one was large and rectangular. The marketplace and parade grounds were sold off, and two additional avenues—Madison and Lexington—were added, as were a handful of squares and public spaces. “How this city marches northward!” wrote George Templeton Strong. It would march northward until it could no further.

The Grid: A Reckoning

After two hundred years, Levitch’s opinion is more-or-less the consensus. The grid, in today’s discourse, is understood as a supreme mistake, a monumental missed opportunity, a hasty job by fantastically dull men. But the “implacable gridiron’s” position in the history of city planning cannot be understated. The grid had to come first so the generations of reactions against it could follow. Through conquering Manhattan, the grid became synonymous with the idea of “the city” in the American imagination; much of what we think of as “20th century planning”—sweeping curvilinear suburbs, tower-in-the-park developments, highways—were less reactions against urban living than they were against straight lines and right angles.

The grid as the original sin of the suburbs and urban renewal is a dark logical conclusion to this exercise. On a brighter note, it is undoubtedly thanks to the commissioners that we eventually ended up with our beloved Central Park. But is Olmstead’s vision truly the urban oasis he imagined it would be? “The park is not a conqueror of the grid but its prisoner,” counters the historian Gerard Koeppel in his book City on a Grid: How New York Became New York. “The exercise yard in a rectilinear penitentiary.”

Aesthetic and functional complaints aside, the most damning condemnations are those that decry the grid’s corrosive effects on the soul. The Manhattanite is suspended in an “immense, malevolent space, in this desert of rock that brooks no vegetation,” according to French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. “Amid the numerical anonymity of streets and avenues, I am simply anyone, anywhere, since one place is so like another. I am never astray, but always lost.” Sartre is describing a kind of dissipation-of-self, of annihilation. But there is something uniquely freeing in finding oneself in the middle of a great expanse, that can induce a self-confrontation only possible in the relative absence of external phenomena. The streets of New York are perhaps the perfect setting, then, to allow one to truly be, by first reducing one to nothingness.

This sensation is not universally emancipating—it certainly is not to Speed Levitch. For him, it is, rather, a daily humiliation: “We’re forced to walk on these right angles,” he says, exasperatedly. The grid is just another force that constrains human creativity and individuality; most importantly, the grid is a litmus test for one’s ability to imagine other possibilities. If you fail to question the grid, if you take it for granted, you’d likely fail to question anything: “I can’t imagine standing on a chair in the middle of a room and changing perspectives,” says Levitch, impersonating this kind of person, “I can’t imagine changing my mind on anything. In the end, I can’t even imagine having my own identity.”

Thinking Off-Grid

So should we do as Levitch suggests and “blow up the grid plan and rewrite the streets, to be much more a self portraiture of our personal struggles?”

Before we do, we should consider that the commissioners’ plan—despite all its shortcomings—does create a unique kind of structural and spacial egalitarianism. In one of his many critiques, Frederick Law Olmstead writes: “If a building site is wanted, whether with a view to a church or a blast furnace, an opera house or a toy shop, there is, of intention, no better a place in one of these blocks than in another.” This exact sentiment can be taken in a more positive light: in a city with so few privileged focal points, in which the plot dimensions are identical from Harlem all the way to Chelsea, Manhattan is in no way without landmarks. Architects and builders simply must do something different to stand out. And one way to do so is by building higher and higher: perhaps it is thanks to the grid that we have our skyline—Manhattan is only uniform in two dimensions.

And for the planner that would rather not “blow up the grid,” Speed Levitch might still be on to something. To never question the grid is to say, quote: “I’m going to relive all the mistakes my parents made … I will do my best to recreate myself, the damages of my life, for the next generation.” For Levitch, rejecting the grid is more about everything the grid represents—dull utility, rushed thoughtlessness, self-serving “best practices,” homogeneity, maximization of profits—and choosing, instead, imagination and creative integrity.

If or when planners actually confront the grid itself, perhaps the single most important, immutable, and overlooked piece of city planning in American history, other big challenges will only feel small in comparison. But if the grid is getting you down right now, that might just mean it’s time for a trip to the park, or up above 155th street. Allow yourself to wander the windy old alleyways of the financial district. Or maybe just look up.