by Selina “S” Heinen

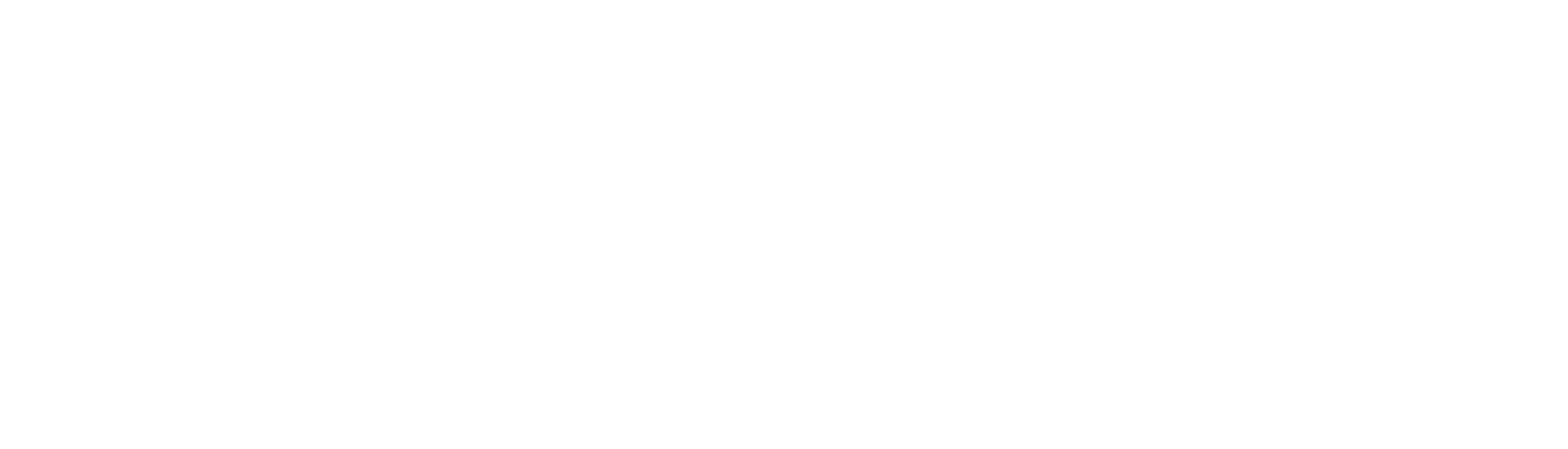

NYC A/C/E subway riders may have noticed the brass-collar workers laboring to keep commuters on track. It may not seem like these sculptures do anything more than take valuable seating, but investments in transit art are placemaking elements crucial for safety, navigation, and a catalyst for economic growth. Transit art installations influence how and where users move through a city, relate to their fellow commuters, and how they interact with the urban environment as a whole. It tells a story about the surrounding communities, often preserving their history—but planners, policymakers, and architects must take measures to ensure that the narrative is an accurate one.

Transit art inspires economic development.

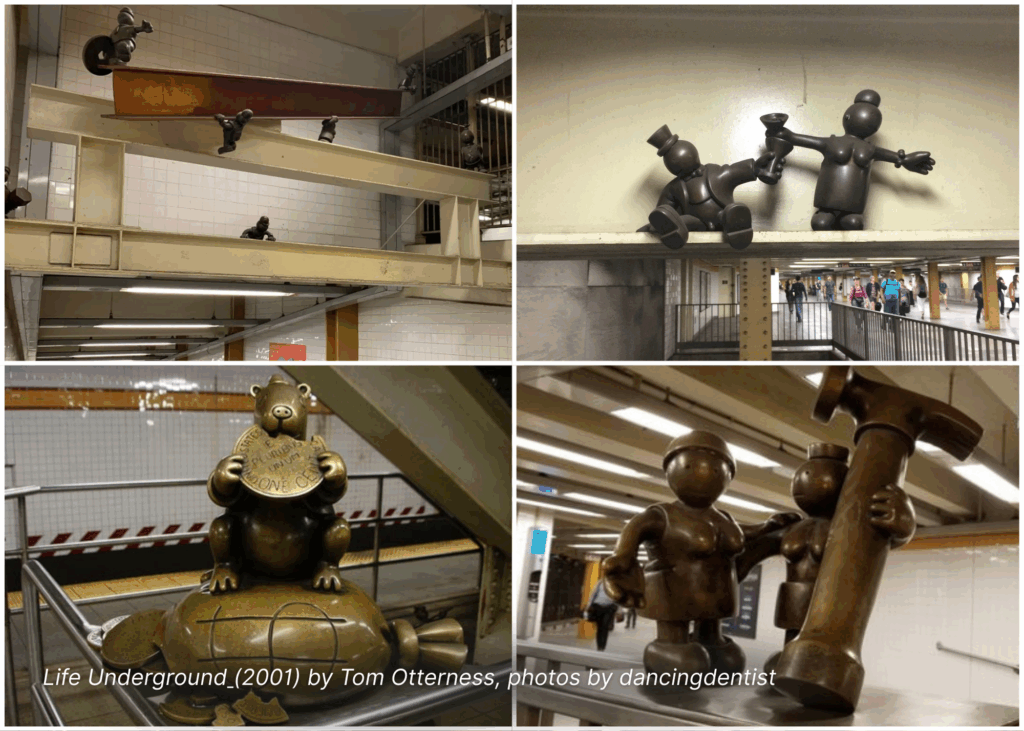

Sightseeing transportation is estimated to make $5.8 billion in 2025, proving that people will go out of their way to visit a beautiful space. When art, like the Tokimeki Fruit-Shaped Bus Stop Avenue, becomes iconic, it attracts tourists who will spend money to see it, again to take a picture with it, and then at shops and food establishments in the surrounding area. The Tokimeki’s Fruit-Shaped Bus Stops were designed to welcome visitors during the Nagasaki Travel Expo, and were such a hit that they were kept and are in use to this day. They are also designed with navigation in mind. On one side of the road is one type of fruit, and on the other side of the road is a different fruit. Riders have an easier time knowing if they are going in the correct direction, reducing confusion and delays, and improving the overall psychological effects of public transit. Transit art is more than a pretty facade. It offers even more benefits than what meets the eye.

Beyond aesthetics, a beautiful environment can also prevent crime and create a safe environment for users. When something appears to be well-maintained, it signals that the area is surveilled. This can deter would-be offenders from taking action in the given area. These benefits are persuasive enough to help secure public funds for transit art and the development of public art programs in general. Due to the power these installations hold, planners must ensure they are equitable, just, and representative of the surrounding neighborhoods, because the consequences could be severe.

If you want art to represent a community, you need community input.

Because transit art can define the area it is attached to, it’s important to solicit community feedback on what designs matter to them. Artists want to be aware of perpetuating stereotypes or excluding and appropriating cultures, as was the case in Calgary, Canada. An American artist from New York was commissioned to design the gateway, “Bowfort Towers,” in Calgary, Canada. The city wanted to link the art to the indigenous Blackfoot people, as the strip of highway lay at the foot of an important indigenous site. The artist “consulted with Blackfoot people, but wasn’t trying to make a Blackfoot sculpture.” However, without proper research, the sculptures did not achieve what the artist and the city hoped. Instead of paying homage, the installation looks like Blackfoot burial towers, invoking an insensitive and macabre image rather than a welcoming gateway. This faux pas could have been avoided with a thorough community engagement strategy, much like the one Public Works is doing for Chinatown Connections.

Public Works Partners is leading a multi-year community engagement strategy with Marvel Designs for another gateway, Kimlau Square. Having recently completed phase one of the engagement process, where we collected community input on what they wanted the communal space to look and feel like, the team is now proposing design elements from Marvel and collecting feedback on what the community wants the final design to hold. In addition to community engagement, the artist who will design the gateway, Jennifer Wen Ma, is someone who has a deep understanding and lived experience around diasporas and identity, and how those play out in place, space, and public art. While this strategy takes time, energy, and funding, the resulting impact will be worth it.

Let’s design neighborhoods for the communities in them.

Stakeholder engagement is the backbone of urban planning. Planners can use engagement as an opportunity to learn how communities want their culture to be reflected in the built environment. Sometimes the solution is whimsical bus stops, and sometimes it is a thoughtful snapshot of history. Regardless, the more a community is invested, the greater the benefits. Beautiful spaces help navigate people because they receive more attention, making them safer for riders, and attracting visitors who spend money in the area. This is why aesthetics should be taken into consideration at every stage of the planning process.