Authored By: Veronica Maisch

New York City has long been home to the largest public transit system in the country. Over 600 miles of subway tracks and over 300 bus routes take millions of New Yorkers to and from work, school, doctors appointments, grocery stores and wherever else they may need to go each day. In fact, only 45% of households in NYC own a car, and fewer than 30% rely on one to commute to work. What’s more, investment in a strong public transit system is a commitment to equity as low-income communities are more likely to rely exclusively on public transit to commute and travel across the city. In many ways, the NYC transit system is among the greatest assets of the City: allowing for high-density housing and commercial development, mass movement of workers across the city, and a sustainable means of transportation that reduces emissions and mitigates gridlock.

The Need for a Resilient Public Transit System

Despite its enduring value to the economy, the environment, and the people of New York, the MTA continues to face shortfalls in funding and sustained investment for capital projects and services–and this just as the impacts of climate change are threatening to further imperil the longevity of the system. On June 5, 2024, New York Governor Kathy Hochul paused the long-anticipated congestion pricing plan that was supposed to begin at the end of that month and was projected to bring in about $15 billion to the MTA capital budget. The congestion pricing plan for NYC has been underway since 2019, and in addition to bringing in a much needed revenue source for the MTA, is designed to encourage public transit use, and reduce vehicle emissions and traffic. On November 14, 2024, Governor Hochul announced that congestion pricing would be instated on January 5, 2025 with a reduced $9 toll from the planned $15. While advocates and critics of congestion pricing continue to argue over its merits, the MTA cannot afford to delay planning and upgrading the transit system to make it more resilient to the effects of climate change.

MTA Climate Resilience Roadmap, April 2024.

In 2012, the storm surge and coastal flooding caused by Hurricane Sandy inundated the NYC subway systems, causing over $5 billion in damages, closing the system for several days, and disrupting service for weeks. The devastation caused by Hurricane Sandy prompted the City and the MTA to take action towards preparing for storm surge events, but more recent flooding events have illuminated increasing vulnerabilities to pluvial flooding–when intense rainfalls overwhelm the capacity of the urban sewer system to drain water away from streets, homes, of course, the subway system. In 2021, rainfall from the remnants of Hurricane Ida dropped more than half a foot of water on NYC in just a few hours, halting the transit system across the city. Rainstorm events in 2022 and 2023 also brought flooding and service disruptions across the city. Each of these events has proven how critical it is to invest in resiliency of the transit system, not to mention studies that project sea level rise to completely swallow subway stations in low-lying areas of the city as well as submerge MTA commuter lines along the Hudson.

So what are some steps we can take to make our transit system more resilient?

Green Retrofits and Urban Design

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, the City has undertaken urban design and retrofit projects to make the subway system more resilient to flooding. Deployable floodproof barriers are now installed across hundreds of subway entrances to prevent the structural damage caused by inundation. In locations most vulnerable to flooding, station entrances have been elevated a step or two to prevent street-level flooding or storm surge from pouring down the station steps. Subway ventilation grates ubiquitous along city sidewalks have been elevated in some flood-prone areas to prevent flooded streets from draining directly into the subway system (and in many cases, these elevated grates have been designed to double as public seating).

MTA Climate Resilience Roadmap, April 2024.

Investing in green infrastructure is another way to prevent the worst effects of flooding on the subway system, but also for surface-level transit like buses, bikes, and pedestrians and of course to prevent flooding in homes and buildings. Green infrastructure is a network of natural and semi-natural designed areas that can help manage stormwater by giving the water somewhere to go. In some cases that can look like retrofitting avenue medians, roadside curbs, or bus stops and parks with rain gardens, bioswales, or planters to retain water during extreme rainfall events so that the sewer system is not overburdened. Reducing impervious surfaces across the city and implementing green infrastructure would go a long way ensuring the resiliency of the transit system in NYC. This strategy would not rely solely on the MTA to implement since it could be (and in most cases already is) pursued by various city agencies such as DOT, Parks, DCP, NYCHA, HPD, DOE, as well as private building and land owners.

Investment in Surface Transit for Greater Resiliency

One of the most difficult arenas for creating a resilient transit system is in the minds of modern users who have experienced delays, disinvestment, and declining service year after year. To ensure the longevity of the public transit system, it must be a reliable, flexible system that users can depend on.

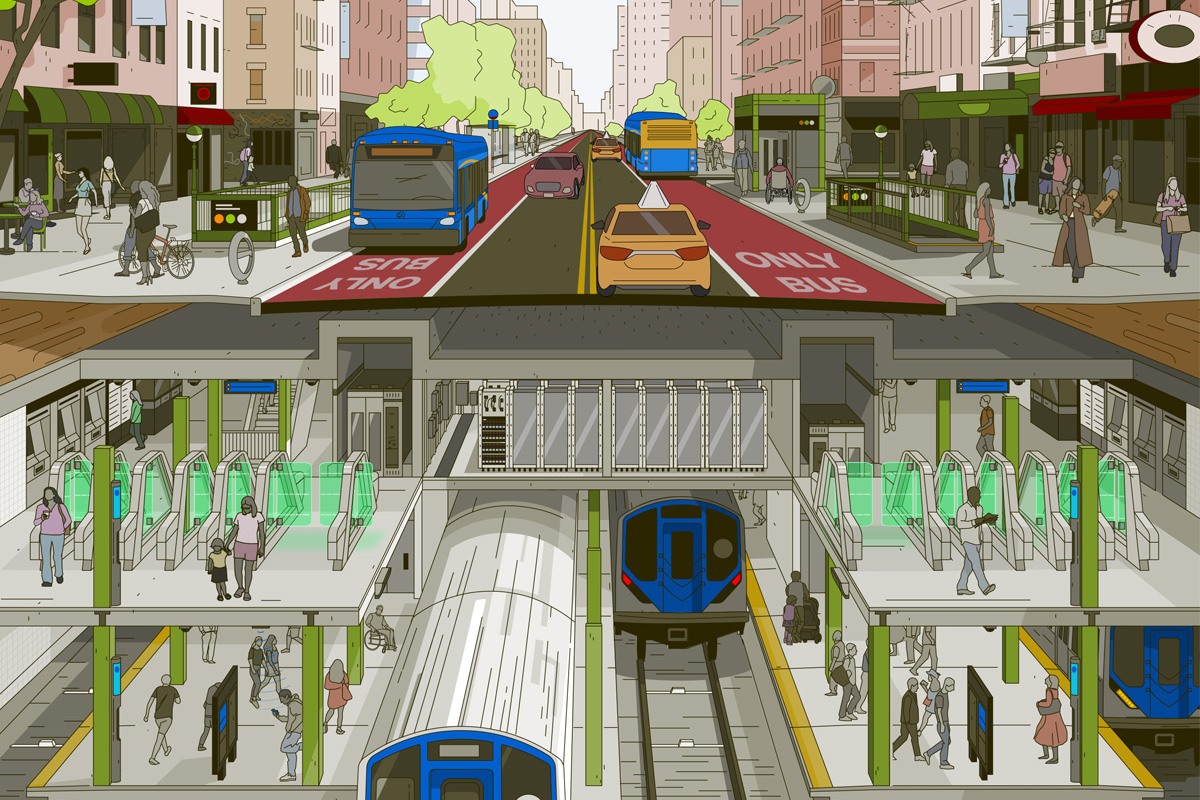

In the days after Hurricane Sandy, for example, subways remained closed while New Yorkers struggled to return to their regular schedules, requiring movement across the city. Walking and cycling became the main modes of transportation, and when private cars threatened to choke city streets with gridlock, the City and State quickly stepped in to require carpooling and to provide priority bus lanes across bridges. Implementing bus rapid transit (BRT) across the city would go a long way to increasing the resilience of the transit system by providing a reliable and fast alternative to the subway when storms require closure, and connecting New Yorkers outside of the subway network to transit hubs. As it stands, the NYC bus system is one of the slowest options for transportation in the City due to vehicle traffic on the roads that causes buses to be endlessly caught in traffic. A true bus rapid transit system would maintain a road lane exclusively for buses (unlike the current bus lanes which are often obscured by double parked vehicles) and prioritize traffic signals for bus movement.

Concept by Urban Design Forum’s Resilient Commutes Working Group. Photosim produced by Stantec. Strengthen Transportation Resilience with Bus Rapid Transit, 2024.

Another strategy for creating a more resilient transit system for users is investing in protected bike lanes and secure bike parking at transit stations. Biking is a natural complement to public transit as it can serve as a feeder to transit stations and increase catchment areas and ridership by relieving first mile/last mile transit burdens. Combined, bikes and public transit are an affordable, healthy, and sustainable mode of transportation. This kind of intermodal transportation can provide a seamless, door-to-door experience that is essential to public transportation’s ability to compete with the ubiquity of private car transportation. Protected bike lanes assure residents that urban cycling is a viable and safe transportation method that they can rely on. If more New Yorkers feel safe navigating the streets on bikes, it would reduce car traffic, which would in itself enhance bus service in the city. Better still, if more New Yorkers feel confident about cycling in the city, and there are easily-accessible, secure places to park their bikes near transit, then public transit benefits directly. The increased options and flexibility that come with bike-transit integration more closely meet the needs of the dynamic pace of urban life in twenty-first century New York City moving towards a more resilient future.

Financing a more Resilient Future

Refrofits, upgrades and infrastructure improvements cost money, and the systematic disinvestment of public transit systems at the city, state and federal levels leave each, including the MTA, searching for new sources of funding.

In 2024 New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy proposed instating a corporate business tax of 11.5% on New Jersey-based businesses with profits in excess of $10 million a year to fund much-needed transportation infrastructure projects. This tax will provide a reliable source of funding for New Jersey Transit at approximately $800 million a year. While approximately 40% of the MTA operating budget is already funded through taxes, Governor Murphy’s aggressive tax on the most profitable businesses in New Jersey provides a model that New York could follow to provide a consistent funding stream for public transit. Alternatively, in 2022, Colorado implemented a retail delivery fee on all vehicle deliveries to consumers within the state. The fee provides funding for highways, bridges, tunnels, electric vehicle charging stations, and projects to reduce air pollution and to electrify vehicle fleets and transit systems. It has brought in more than $160 million.

Finally, no transit financing discussion can be complete without considering The High Cost of Free Parking: the title of Donald Shoup’s 2005 book which argues that street parking in cities is a valuable public asset that deserves to be priced as such. Recently interviewed on NYC DOT’s podcast Curb Enthusiasm, Shoup’s research continues to prove that street parking reform is a critical issue for cities and public transit systems to undertake. Although eliminating free street parking would undoubtedly create pushback similar to that against congestion pricing, there is no denying that there is a clear opportunity for the city to generate a reliable revenue source to invest in valuable public transit and transportation projects.