The future of transportation is here—and it’s not self-driving cars or Hyperloop—but green mobility. Cities across the world are embracing a future of mobility that prioritizes pedestrian-friendly green pathways, bicycle lanes, and eco-friendly transportation infrastructure.

Current transportation systems contribute to fossil-fuel emissions and aid in degrading air quality. Moreover, the present system also leads to noise pollution, water pollution, and affects ecosystems through multiple direct and indirect interactions. Yet, how do we combat this when transportation and mobility are essential aspects of our everyday life? With transportation so embedded into our cultural environment, embedding new transport systems into our natural environment seems the answer.

Green mobility encourages modes of transport that are not dependent on fossil fuels for operations and promotes the United Nations (UN) concept of “Moving People than Vehicles.” The four main pillars of the UN aim to avoid, shift, integrate, and innovate.

Avoid: excessive motorized vehicle

Shift: from unsustainable modes of travel to more sustainable means

Integrate: the various transportation modes available in a city

Innovate: giving a new perspective to existing transport modes

Localized efforts have taken place on almost every continent, yet significantly in New York City and Bogota, Colombia. Steering away from conventional transportation models and into sustainable alternatives guided by green mobility, New York City and Bogota offer an approach to reshaping transportation for their citizens.

New York, NY

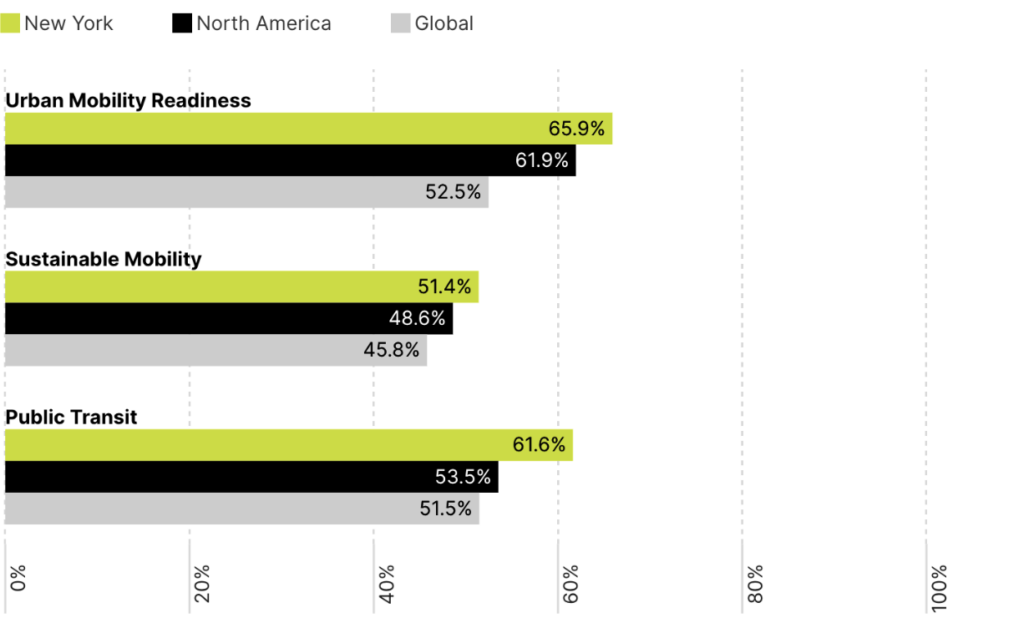

According to the OliverWyman Forum, New York is ahead in the urban mobility readiness index and sustainable mobility and public transit scores. From investments to resources, the city trumps the continent and other parts of the globe.

A key component of this high score relies on the CitiBike rideshare program. Beginning in May 2013, the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) partnered with Citibank in launching the bike share program in New York City. Since beginning with stations only in Manhattan and Brooklyn, the program has now grown from 6,000 bikes to 26,000 bikes in the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens, as well as in Jersey City and Hoboken, New Jersey.

The expansive network has pushed the city to increase cycling infrastructure, with much of it coming from the NYC Streets Plan, which legally mandates the installation of at least 50 miles of protected bike lanes every year from 2023 to 2026. Websites like Transportation Alternatives track this development, updating the public on the project’s announcements, progress, and successes.

Moreover, the integration of the bike program with the public transit system allows for the program to add additional mobility for riders. Many struggle with the “last mile,” a concept that refers to the distance between a transit stop and a passenger’s final destination. While public transit often covers large distances efficiently, access is not always convenient in every neighborhood. Thus, the Citibike program allows users to finish that final mile through cycling.

The Green Rides Initiative also aids in New York’s attempts at green mobility. By 2030, all rideshare trips must be conducted by either zero-emission or wheelchair-accessible vehicles. With yearly benchmarks for Uber and Lyft starting from 5%, the goal is to slowly transition the city’s rideshare trips. The program aims to remove an estimated 60,000 metric tons of carbon annually from New York City’s air.

Bogotá

Previously called one of the most congested cities in the world, Bogotá, Colombia, has been making strides with its green infrastructure. The Corredor Verde, or Green Corridor, is a program that includes 22 kilometers of green pathways.

The Mayor of Bogotá, Claudia López, bases the project on “three pillars: more and better public space, sustainable mobility and ecology.” With the completion of the corridor, travel by public transit should be reduced by half and private vehicles should reduce their trips by 20%.

However, Ciclovía, an official program of the city government and supported by the Transportation Department, has been happening since 1976. Every Sunday and public holiday from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., certain roadways are blocked off to cars to allow runners, skaters, and bicyclists to exercise.

Four decades strong, the event has entirely shaped a generation that now looks at the streets differently. People of all ages take to the streets every Sunday, creating an authority from a young age to feel comfortable and empowered in public spaces. Yet, it wasn’t simply the Sunday bike ride that altered Bogotá’s cycling culture, it was former Mayor Enrique Peñalosa.

During Peñalosa’s first term between 1998 and 2001, “300km of protected bidirectional bike paths were created, connecting the poorest parts of the city to the centre, the network was comprised of main, secondary, and complimentary tracks.” In 2020, Mayor Claudia López, who is responsible for Corredor Verde, continued to add 280 km of bike paths. Today in Bogotá, there are over 600 km (372 miles) of roads for cycling.

Ciclovía and the investment into cycle infrastructure have completely altered the culture in Bogotá. Today, residents can choose green options as they move from Point A to Point B.

Conclusion

As we look toward the future of transportation, it’s evident that green mobility is not just a trend but a real step forward in making our cities more green. The examples set by both New York and Bogotá speak to a transformative power of prioritizing sustainable transportation options and their possibilities.

However, progress still needs to be made – for more cities to follow suit and prioritize investing in pedestrian-friendly pathways, bicycle lanes, and eco-friendly transportation infrastructure. The future of transportation may be here, but it’s far from present in most cities.